We’ve all seen this situation up close. A friend – smart, capable, high-energy – ends up in a relationship that is clearly running his entire life, and everyone around him can see it except him.

In the beginning it was romance, adrenaline, “she’s incredible.” A couple of years later he’s become the secondary character in his own story. The disaster isn’t loud – it’s gradual. Growth stopped. The sharp edge is gone. He doesn’t look as put together, doesn’t train, doesn’t recharge, doesn’t protect his time. His numbers at work slide, his focus is scattered, and his private space has officially left the building.

Brokerages, TPAs, and stop-loss teams fall into the exact same dynamic with certain clients.

One high-drama small group or one oversized, high-control account starts running the emotional climate of the firm. Everyone adjusts. Leadership, service teams, operations – the whole organization begins orbiting one behavioral gravity source. Growth slows, outreach weakens, creativity disappears, and the explanation becomes “market conditions” instead of “relationship conditions.”

Many firms tell themselves they’ll replace these clients when new ones arrive. New ones rarely arrive because the energy required to attract them is being burned daily inside the existing chaos. Consider this article a friendly industry intervention. Some readers will recognize the symptoms immediately. Others will run the audit and feel deep relief that their client relationships are healthy. Both outcomes are useful, and considerably cheaper than another year of pretending everything is fine.

The most dangerous client rarely looks dramatic on paper. The real risk sits with the account you feel financially or emotionally unable to challenge – the one that quietly defines your tone, your priorities, and the future of your company.

The Growth Killer Hiding in the Morning

I’ve seen this pattern repeatedly while working side by side with veteran brokers a couple of years ago – people with 15, 20, 25 years in the business. Not beginners. Not disorganized rookies. Seasoned operators. We set up structured morning prospecting sessions together – real outreach blocks, real growth work. They would make calls, I would listen live, drop feedback in chat, adjust wording, refine positioning on the go. Clean system. Clear objective. Strong intent.

On paper, it was perfect. In reality, it almost never worked, specifically in the morning. Because the phone would not stop ringing.

Every incoming call arrived labeled urgent. Every situation came wrapped in emotion. Every issue demanded immediate attention. Even when the broker clearly understood the problem was administratively small – a deductible confusion, a coverage timing issue, a plan-usage misunderstanding – they still stopped everything. Prospecting paused. Outreach died mid-sentence. Growth work got pushed aside for “just a quick fix.”

We would reset and restart. Within minutes – another interruption. Same pattern. Same urgency. Same emotional weight.

So we started checking where the noise actually came from.

Not the 300-life group.

Not the 500-life group.

Not the structured HR teams.

It was the micro-groups.

Three lives.

Five lives.

Ten lives.

Again and again.

Small groups generating maximum emotional amplitude and minimum revenue weight — and still controlling the prime growth hours of the day. The brokers would say, “Fine, we’ll prospect in the afternoon.” By afternoon, the psychological fuel tank was empty. No edge in the voice. No persuasive energy. No appetite for rejection or negotiation. Outreach technically happened – performance didn’t.

And here’s the important emotional truth for leaders in broker, TPA, and stop-loss organizations: this doesn’t feel like a structural problem when you’re inside it. It feels like responsibility. It feels like being needed. It feels like service. Meanwhile, day after day, the activities that actually grow the firm are being displaced by low-revenue, high-noise interruptions.

When that pattern repeats systematically, growth doesn’t slow by accident: it gets scheduled out of existence. That’s not a discipline failure. That’s a portfolio design failure wearing a customer-service badge.

Now Available on Amazon

Survivors inventors

A powerful playbook that shows you how to read every prospect’s mindset, smash through resistance to change, and unlock a clear vision of your brokerage’s future.

What Proactive Actually Looks Like (My Version)

Back in 2013, when I started running my insurance brokerage company, my competition were two experienced brokers with certain number of clients (not many, but they were doing better that me, as my number was 0 at that time), and international backup (they were branches of two international companies). In less than 2 years, I got the biggest and the most desirable projects on the market. How?

At the tender stage, we didn’t promise “great service” and faster email replies like everyone else. We proposed a proactive claims-management model. Weekly monitoring. Physical presence. Real human contact. We told them upfront: we are not going to wait for problems to explode – we’re going to walk the floor and catch them early.

From day one, we sent our people on site – sales managers together with a claims manager – directly into the factories, offices, buildings, areas where the employees operated. My team didn’t sit in meeting rooms. They walked around and talked to employees face to face. Simple questions: Have you used the healthcare plan? What happened? Where did it get stuck? What was confusing? Most issues were solved right there with explanation and navigation. When something required backend work, they collected the details, took contacts, came back to the office, and pushed it through properly.

Yes, it was an investment on our side: it cost time, payroll hours, operational focus. It was also part of the strategy, not charity. We built it into the model from the start.

The effect after a few months was striking. Employees knew exactly who we were. They knew our names, our role, how to reach us, how to explain their issue, who to call and when. The quality of inquiries changed. The tone changed. Panic turned into process. Friction dropped because understanding increased.

Years later – after long cooperation – many employees barely knew which insurer stood behind the plan. They never needed to call the carrier directly. Everything flowed through a structured broker channel because trust and clarity were already built. Service became predictable because education was continuous.

That’s what proactive looks like in real insurance operations. You invest early, you reduce noise later. You design behavior instead of chasing it. The same logic applies to business development itself – firms that continuously build acquisition capacity and market presence serve their existing clients better, not worse. Growth discipline and service quality reinforce each other when the model is designed on purpose.

The Large Account Illusion

There’s another danger zone in this industry, and it’s the one people avoid discussing because on paper it looks like success.

The big account. The flagship group. The name you’re proud to put on a slide. Strong revenue, stable relationship, predictable renewals. Everything looks solid, and that’s exactly why it’s dangerous.

Large accounts don’t usually damage firms through conflict. They do it through comfort.

I’ve watched this pattern play out more than once. A broker, TPA, or stop-loss carrier lands a major group and the internal temperature changes. The urgency to market cools down. Outreach slows. Partner development becomes optional. Acquisition activity turns into a “when we have time” project. Public presence goes soft and generic – safe posts, harmless quotes, broad education pieces that offend no one and attract no one. The internal story sounds reasonable: we’re busy, revenue is stable, let’s not overload the system.

That’s the moment the “good enough” phase begins, and good enough is one of the most dangerous conditions a business can enter.

Because business is not a parked car. It’s either moving forward or rolling back. The idea that a firm can pause growth and simply maintain position sounds logical and fails in practice. The moment growth stops, competitiveness starts declining: quietly at first, then visibly.

Dependence forms next, and dependence edits behavior. The large client becomes the center of gravity. Priority distortion appears. Exceptions become normal. Boundaries soften. Internal teams hear the same coded message again and again: make it work – this account matters. Fear of losing the client turns into unofficial policy, even if nobody uses the word fear.

Then a second-order effect hits – talent quality starts slipping.

High-level people want to grow. Strong operators want momentum, challenge, expansion, movement. When a firm stops growing, it becomes less attractive to top talent. Recruitment gets harder. Retention gets weaker. The people you most want to keep start looking around. That directly affects service quality, including for the very large client the firm is trying so hard to protect.

So the paradox appears. By slowing growth to “protect” the big account, the firm reduces its ability to serve that account at the highest level. Less competitive hiring. Less innovation. Less sharpness in the market. More operational fatigue. The risk increases while everyone believes they are playing it safe.

And then comes the event nobody plans for. The large client leaves. Acquisition. Leadership change. Consultant switch. Board decision. Broker change. TPA change. These moves rarely come with generous warning periods. From the client’s perspective, it’s a business decision. From the dependent firm’s perspective, it’s an earthquake.

Now growth must restart from zero – with a weak pipeline, muted market presence, and a team that hasn’t exercised acquisition muscles in years. Recovery is rarely measured in months. It’s usually measured in years, sometimes with layoffs in between.

A firm supported by one or two dominant clients doesn’t really own a business. It operates a sophisticated job – with staff, overhead, and risk – but without true strategic independence.

In prospecting, patience is the tax you pay for real influence.

Margo White X

Bad Clients Are Often Enabled

Most people talk about “bad clients” as if they arrive fully formed – like a weather event or a genetic condition. Field reality looks different. In many cases, the client isn’t universally difficult. The client is situationally difficult, and the situation was built during the sale.

I’ve watched this pattern repeat across brokers and stop-loss carriers. The deal phase starts, excitement goes up, caution goes down. The broker wants the group, wants the logo, wants the revenue, wants the win. The tone shifts without anyone naming it. The conversation starts sounding less like a professional engagement and more like an audition. Promises expand. Flexibility becomes unlimited. Access becomes personal. Everything is “yes.” The underlying message – even if never spoken – lands clearly: you are the prize, we are lucky you picked us.

Clients read that instantly.

From that moment, the power structure is set. The client feels like the selector. The broker feels selected. Behavior follows structure. Demands increase. Respect decreases. Boundaries feel optional. Every exception looks reasonable: after all, you promised everything at the beginning. Later, when service teams try to introduce process, timelines, or communication lanes, it feels to the client like quality is dropping, when in reality structure is finally being introduced too late.

Now look at the opposite pattern. Advisors who walk into the relationship with calm authority, clear value language, and defined operating rules produce very different client behavior. They explain how service works, where issues go, who handles what, and how escalation flows. They don’t posture. They don’t beg. They don’t perform. They describe value and structure with confidence because they’ve done it before and know the financial and operational impact of their work.

Serious business leaders recognize that tone immediately. They run companies themselves. They understand process, chain of command, and service architecture. They don’t expect executive-level interruption for every participant question. They expect a working system.

Think about how behavior changes in high-standard environments. Walk into a top luxury boutique and start shouting at staff – access disappears fast. Not because the brand is arrogant, but because the brand is structured. Standards are visible. Behavior adjusts automatically around standards.

The same mechanism works in client relationships. Where standards are clear, behavior improves. Where everything is negotiable, chaos applies for permanent residency.

Boundaries introduced before signature feel professional. Boundaries introduced after chaos feel defensive. Timing decides whether structure earns respect or resistance.

Marketing is optional. Prospecting is Oxygen.

The 90-Day Client Reality Audit

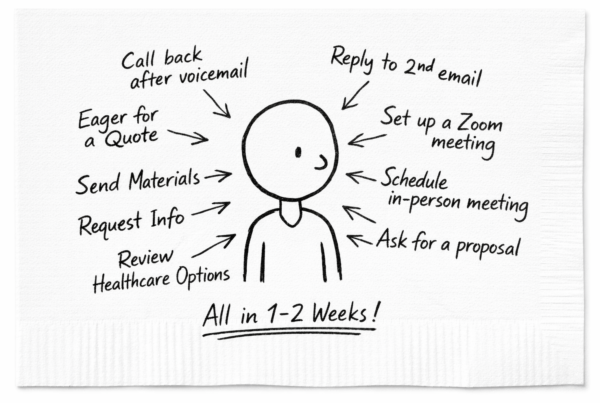

Before anyone starts talking about cutting clients, walking away, or “cleaning the book,” slow down and do something far more powerful – run a structured audit. Not an emotional reaction after a bad week. Not a dramatic decision after one ugly call. A disciplined, operational review over a fixed window. Ninety days is usually enough to expose the truth.

Because here’s what actually happens in most firms: leadership feels drained, teams feel overloaded, growth slows – and everyone speaks in generalities. “This client is difficult.” “That group is heavy.” Generalities protect denial. Measurement removes it.

For the next 90 days, treat your client portfolio like a dataset, not a relationship. Observe behavior the way an operator would, not the way a stressed human would. You’re not judging: you’re recording.

Track interruption and escalation patterns account by account. Look at how often work gets broken, not how loud the last incident felt. Pay attention to how frequently normal workflow gets hijacked and who gets pulled in when it does. Notice which accounts repeatedly drag senior people into issues that should live at service level. Compare the service gravity of the account with the revenue it produces. Many surprises show up right there.

In practical terms, you’re watching things like:

- how many unplanned escalations happen per account

- how often your day gets interrupted by that client

- how many “urgent” issues arrive after hours

- how often tone crosses professional boundaries

- how frequently leadership – not service staff – must step in

- how much service time the account truly consumes

- how often prospecting, marketing, or partner work gets postponed because of them

Now add a second lens for large accounts, because their risk profile is different. Big groups rarely create constant noise, they create silent dependency. So here you measure exposure, not interruption. Look at revenue concentration. Look at how many process exceptions you grant them. Look at whether your acquisition and partner-development activity has slowed since they became dominant. Then ask a hard scenario question: if this account left in six months, how full is your pipeline today – really?

This audit changes conversations inside a firm. Vague frustration turns into visible patterns. Emotional narratives turn into operating facts. Most leadership teams discover that a small percentage of accounts generate a large percentage of cognitive drag, and that one or two large clients quietly control strategic behavior.

Once the numbers are on the table, denial has nowhere comfortable to sit. Patterns become obvious very quickly – and once seen, they’re difficult to unsee. That’s exactly the point.

Prospecting Calculator

Run Sales Simulation

In seconds, you’ll see your future numbers, the deals you could unlock, and how sticking to the right targets reshapes your entire business.