When I was little, I heard a phrase over and over again:

be careful what you wish for.

I didn’t understand it then. Wishing felt harmless. Logical, even. You want something better, you imagine it, and somehow the world is supposed to meet you halfway. It took growing up to realize the problem with wishes isn’t desire, it’s that we rarely unpack what the wish actually implies. We picture the outcome and conveniently ignore the chain of events required to make it real.

Brokers do the same thing. They wish for an ideal client without thinking through the conditions that would have to exist for that client to behave the way they imagine. But we don’t live in a world where outcomes appear in isolation. Every result has a backstory. One thing always leads to another. And when you slow down and trace that chain, the Q4 unicorn prospect starts to look less like opportunity, and more like misunderstanding of how real organizations actually make decisions.

Let’s start with the fantasy.

Brokers love the idea of the perfect prospect. The one who listens attentively in the first meeting. The one who nods at all the right moments. The one who hears the words

“overpriced fully insured plan,” “transparency,” “control,” “self-funding,”

…and suddenly freezes like Neo in The Matrix.

You’re Morpheus.

They’ve just taken the red pill.

Their eyes widen.

Healthcare… makes sense now.

They weren’t looking for change. They weren’t talking to anyone else. No broker has ever explained this to them before. You called at exactly the right moment. One meeting later, the deal is basically done.

This is the mental movie most brokers are running while they’re dialing.

It’s also almost entirely fictional.

The Q4 Unicorn Prospect

Let’s step outside the call script for ten seconds and watch this like adults. Reality check.

The Q3/Q4 dream prospect for brokers is the one that’s ready to change – but isn’t looking for options and actively comparing brokers (because no one dreams of competition).

Nobody ever approached them, but they are a desirable prospect, care about their employees, and have a vision big enough to plan for a few years ahead at least .

They’ve never heard about self-funding – at least not in the exact phrasing you use, with your exact angle, and your exact “let me just walk you through this spreadsheet” enthusiasm. And yet… the moment you show up, they’re ready to hand you one of the most sensitive financial decisions in the company because you “called at the right time.”

That is the elephant in the room. Organizations do not behave like that. Not serious ones. People don’t wake up randomly and rewire their benefits strategy because a stranger explained that fully insured is “overpriced” and self-funding is “transparent.”

If a company truly hasn’t been approached, truly hasn’t been educated, and truly isn’t shopping, the odds are you’re looking at a small group – five lives, ten lives, maybe twenty.

And there’s a reason big insurers and serious brokers aren’t camping outside their door. These clients are simply not profitable. They’re noisy. They take a lot of energy. They’re unstable.

And that’s where the numbers-game broker lives. The one who thinks volume is a business model. Fifty calls. A hundred calls. Twenty today, thirty tomorrow. Start “really prospecting” in September. Get closer to renewal and hope fear does the selling for you.

That’s not a strategy. That’s a stress disorder with a headset.

So before you crown the “easy win” as the primary source of income for your business, it’s worth looking at what those clients, most of them, at least, actually represent.

And more importantly, what building your prospecting life around that slice of the market does to a broker over the long run.

Now Available on Amazon

Survivors inventors

A powerful playbook that shows you how to read every prospect’s mindset, smash through resistance to change, and unlock a clear vision of your brokerage’s future.

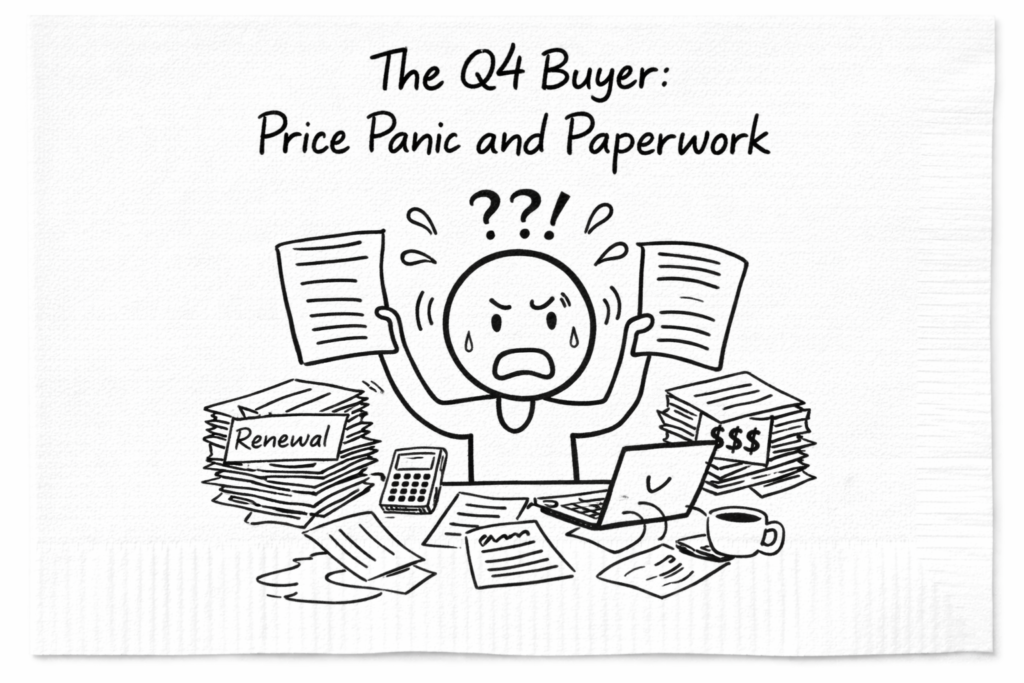

1. The Q4 Buyer: Price Panic and Paperwork

Ready-to-buy prospects come in two types.

Type one is the honest ready-to-buy buyer. They’re ready because the pain finally got loud enough.

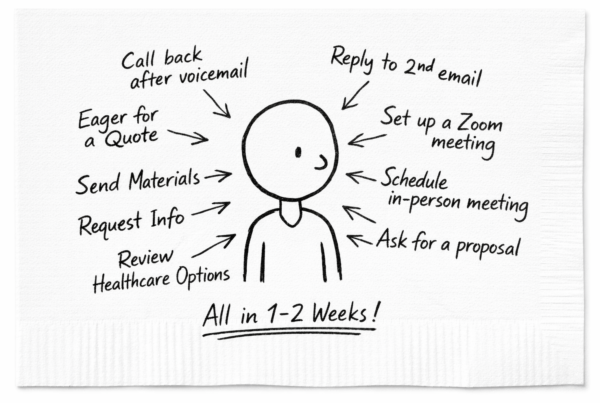

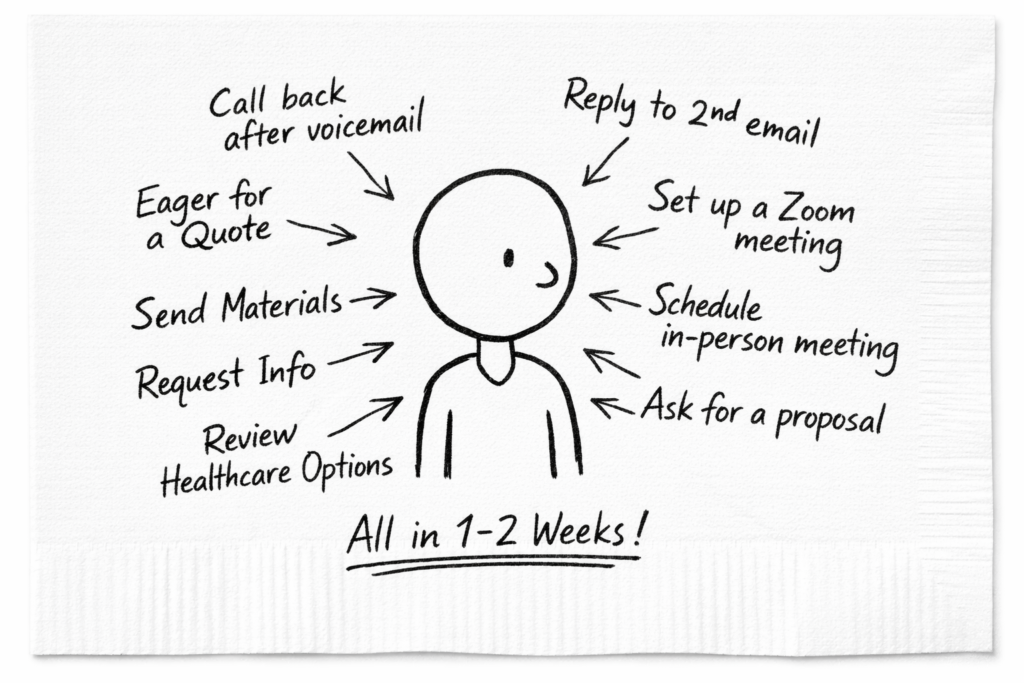

In self-funding, this is often triggered by a fully insured renewal that jumps 20-30% and suddenly turns “we’re fine” into “we’re not fine.” At that point, they’re not looking for education. They’re not looking for a grand philosophical journey from fully insured to self-funded. They already made the internal decision: “This can’t continue.” Now they’re shopping for the best way out – Googling, asking for references, collecting vendor comparisons. You’re not leading them through a transition. You’re helping them execute one they already chose. Which means you’re not a strategist in their eyes, you’re a spreadsheet.

Nothing is wrong with that buyer, but you need to price it correctly in your mind. If they chose you because your numbers were the most attractive under pressure, they can replace you under pressure too. And self-funding is full of moments when things shift – claims experience, renewals, performance conversations, plan design changes. A buyer who hired you as a solution to a price problem will keep you employed only as long as you keep being the best price solution. That’s the relationship. Not trust. Not loyalty. Math.

Type two is more common than brokers admit: the buyer who already picked someone. They’ll still take your meeting. They’ll still ask intelligent questions. They’ll still request quotes and materials with impressive enthusiasm. But they’re not shopping. They’re documenting. They need to show a board, a CFO, or an internal committee that they “considered multiple options.” You’re not competing; you’re helping them check a box. Meanwhile the real winner is usually the broker who’s been present for months, sometimes years, long before this company became “ready.” That broker didn’t show up at the moment of urgency. They were already in the room when urgency arrived.

Most brokers chase the 3% because it feels efficient. It’s not. It’s just immediate. And immediate is seductive when you’re tired, behind, or running your business quarter to quarter.

2. Accidental Conversion

And just like that, brokers end up playing the 3% game by accident. They don’t plan revenue. They don’t model what their book will do this year. They don’t really know if they’re going to grow, because growth, in that setup, is basically a lottery ticket.

It depends on whether the first or second call lands on the exact week a prospect’s renewal notice shows up with a 20-30% spike and the company suddenly says, “Fine. We’ll listen.” That’s not a pipeline. That’s living on timing. And timing, in this industry, is usually spelled Q4.

If you wanted to make that 3% chase predictable, you’d need volume. Real volume. Call-center scale. Interns doing outreach. SDR layers. A follow-up engine that doesn’t get tired, doesn’t get emotional, and doesn’t “take it personally” after the twentieth company rejection before they drink their first coffee.

Large insurers can run that machine because they built a farm system: the small-group world is where new reps learn the game before they graduate to larger accounts. It’s a training ground.

And the strange part is how many full-grown professionals spend their entire careers trapped in that same training ground, not because they’re incapable, but because no one ever handed them a different model.

They were taught a simple formula: make more calls, get more quotes, and when someone says “no,” move on immediately. Treat rejection as the end of the story. Don’t study the account. Don’t watch for triggers. Don’t stay present. Just dial again.

That advice wasn’t just incomplete, it was strategically expensive. Because it trained brokers to abandon the very prospects that become valuable later, and to build their entire income around the smallest, noisiest, most price-sensitive slice of the market.

3. How Small Groups Keep Brokers Small

If you watch a broker operating inside the numbers game from the outside, the pattern becomes obvious very quickly.

Every “no” is treated as a closed door. Every hesitation is interpreted as wasted time. Conversations are short, follow-ups are mechanical, and anything that doesn’t move immediately gets dropped.

Not because the broker is careless, but because the model they’re running punishes patience. You can almost see the internal clock ticking: this isn’t converting fast enough, move on. Over time, that habit hardens. The broker stops building deals and starts rotating prospects.

What’s happening psychologically is subtle but brutal. The broker is training themselves to avoid depth. Long conversations feel expensive. Staying present with an account feels risky. Any relationship that doesn’t promise a near-term win starts to feel irresponsible.

So they stay busy, they stay reactive, and they stay locked into short cycles. From the outside, it looks like productivity. In reality, it’s containment.

Because that way of working creates a massive gap between the broker and the kind of client that requires consistency, restraint, and long-term positioning – exactly the clients who sit in the 100+ and 500+ group range.

This is also where the industry structure quietly works against them. Large insurers are perfectly comfortable letting small brokers “own” small groups.

It keeps everyone occupied. You get a quick win today, a little revenue now, a sense of momentum – and in exchange, you remove yourself as a future competitor for the accounts that actually matter.

You’re busy solving small problems while the profitable, strategic projects stay out of reach.

Not because you’re excluded, but because the model you’re running makes it impossible to ever show up differently.

Fast money has a way of costing far more later, and most brokers don’t realize the trade they’re making until the ceiling becomes impossible to break.

4. Dormant: The Not-Shopping-Yet Prospect

Dormant prospects are where the real 100-plus-life market actually lives. They’re not in the 3% “ready-to-buy” bucket today, but they’re on track to enter it within the next 9 to 36 months. The only problem is they don’t know it yet., or they know it in the vague, inconvenient way people “know” something when they’re not ready to make it today’s priority.

So they do what companies do best: they postpone.

They reject offers from brokers and market participants, push meetings away, and say things like, “Call us back in six months,” or “Not this year,” or the classic, “We’re fine.”

Doorman 100-plus-life groups are worth approaching for one simple reason: the time you invest actually turns into an asset. The outcome is bigger, and the relationship lasts longer.

These are not accounts that churn because someone got emotional about a renewal or because a cousin forwarded a cheaper quote. They choose slower, they choose more carefully, and once they choose, they tend to stay. A five-year tenure is common in this tier. Compare that to small groups that can leave next year – or in two – because they didn’t like a service issue, a billing hiccup, or the fact that a competitor promised a slightly prettier number.

And the best part is how much competition you eliminate before you even “win” anything.

Think about what happens to most brokers the moment they hear, “No, we’re fine.”

They don’t have a system for what happens after that sentence, so they treat it like a dead end.

They move on. They don’t follow up with structure. They don’t stay present. They don’t build familiarity. They just keep dialing until they find someone already panicking.

So when you deliberately choose dormant prospects, 100+ groups that are not shopping yet, but are heading there, you immediately step out of the crowded room. You’re not competing with the best brokers. You’re competing with the broker’s attention span. And most of the market loses that competition all by itself.

This is why those projects feel “dormant” at first. They’re dormant because the company hasn’t announced urgency yet. They’re dormant because the internal pressure is still building quietly. They may reject you today and still be a perfect client later. But when the timing shifts – and it will – the game is completely different than in the small-group world. In this tier, it’s rare that someone walks in with a slightly better spreadsheet and simply takes over your project. That’s not how serious employers choose partners. They don’t swap stewardship for a pair of numbers. They swap only when trust breaks or when the broker was never trusted in the first place.

So the doorman strategy isn’t “be patient” as a personality trait. It’s a competitive weapon.

You pick prospects with real upside, you stay present when others disappear, and by the time the company becomes “ready,” you’re not a stranger with a proposal. You’re the familiar expert they already associate with competence – someone they can safely choose and keep.

Did you really make that choice?

With all this talk about 100-plus-life groups and long games, it might sound like I’m criticizing small brokers.

I’m not. Small brokers should exist. They matter. They serve parts of the market that would otherwise be ignored, and they often do real, meaningful work for companies that need hands-on help.

If that’s the business you consciously chose, and you enjoy it, there’s nothing wrong with staying there.

What I do see, over and over, is something else. Brokers don’t usually choose that lane. They fall into it. And when you talk to them long enough, you realize they didn’t sit down one day and decide, “I want to build my entire career around 5-, 10-, 20-life groups.” It just happened. Scripts happened. Cold calling happened.

Someone told them that more calls equal more money, that rejection means move on, that speed is safety. And they ran that model until it quietly became their ceiling.

What’s interesting is that every broker I’ve personally spoken to, Every. Single. One, admits the same thing when you ask the question directly. They would trade ten 20-life groups for one 200-life group without hesitation. Less chaos. Fewer fires. More leverage. They know it. They feel it. Which tells you something important: the issue isn’t capability. It’s conditioning.

The industry trained a generation of brokers to think like telemarketers. Robotic scripts. Volume worship. Arithmetic growth. Work harder, call more, repeat. But this business doesn’t grow arithmetically. It grows geometrically. Standards compound. Positioning compounds. Trust compounds.

If I had believed otherwise, I would never have landed a 3,600-life group as my first project in healthcare back in 2013. I had no team. No infrastructure. No long résumé in healthcare. On paper, it made no sense.

What made sense to the people across the table was something else. I convinced them of two things.

First, that I would always act in their best interest. And second, that whatever problem came up, I would solve it – no matter the cost.

That was enough. That deal led to the next one. Then PwC. Then the American Chamber of Commerce. Then an G-Airways. And after that, momentum takes over.

That’s the part most brokers never get to – not because they can’t, but because they were never taught to aim there. This isn’t about abandoning small clients. It’s about choosing your trajectory consciously.

Deciding whether you want a business built on volume and urgency, or one built on trust, patience, and scale.

The market will happily let you stay busy forever. Breaking out of that is a decision.

Laser Prospecting is not about avoiding rejection. It's about refusing to let rejection reset your strategy.

Margo White X

Prospecting Calculator

Run Sales Simulation

In seconds, you’ll see your future numbers, the deals you could unlock, and how sticking to the right targets reshapes your entire business.